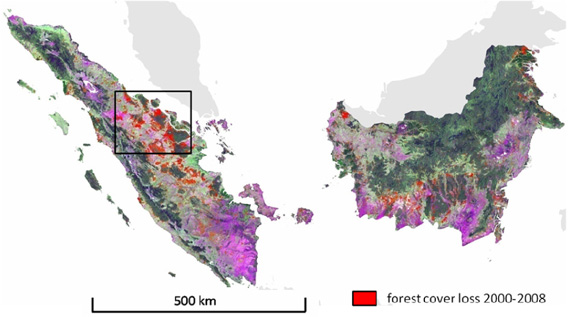

スマトラ島、カリマンタン島の2000年から2008年までの間で減少した 森林面積を表した地図 (2000年から2008年のデータとランドサット衛生写真とを重ね合わせ、中程度の空間分解能で位置精度を表し作成された合成写真 bands 5/7/4 as R/G/B) 地図および情報提供:Broich 2011

インドネシア領カリマンタン島とスマトラ島では2000/2001年から2007/2008年までに54,000km2 つまり面積の9.2%になる森林が伐採された事が衛生観測写真を使用して行われた評価により明らかとなった。

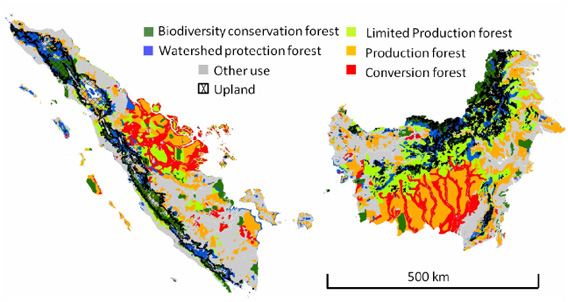

サウスダコタ州立大学のMark Broichのチームによって行われた研究は、森林伐採による開発が規制または禁止された場所において20%以上の森林が伐採されたことを明らかにした。これによれば、インドネシア政府の森林法の強化はどうやら失敗したようだ。

「私たちが行った分析では、森林伐採が許可されている地域ではそのほとんどの森林(79.9%)が伐採され、規制や禁止がされている地域でも20.1%の森林が伐採されている事がわかりました。」と研究の著者は言う。インドネシアの法律では、保安林、保全林、そして限定生産林の伐採は違法である。

スマトラ島とカリマンタン島の開墾許可地域 (Ministry of Forestry Indonesia 2008) と 高知を表す地図 緑:生物多様性保全林 青:水源涵養林 黄緑:限定生産林 橙:生産林 赤:伐採地 地図および情報提供:Broich 2011

森林減少の度合いはスマトラ島の方が高く、大規模に伐採された土地は、パルプや紙原料となる木の植林、またはパームオイル農園となった。スマトラ島とカリマンタン島の両島は、開墾のための野焼きに悩まされている。

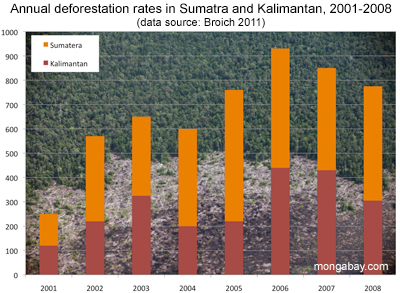

この研究によって明らかとなった数字は、国際連合食糧農業機関(FAO)が想定した結果よりも深刻であった。FAOの想定では、インドネシアは2000年から2010年の間で失った森林面積は年間平均485,000ヘクタール(48,50km2 )であった。

Broish氏の研究が割り出した2000/2001 から 2007/2008の8年間で失われたの森林面積の年間平均は、スマトラ島とカリマンタン島だけでも675,000ヘクタール(6,750km2 )に及んだ。

2001年〜2008年の年間森林伐採率を表すグラフ

2001年〜2008年の年間森林伐採率を表すグラフ

しかし、インドネシアは最近、森林伐採緩和に興味を示し始めている。2009年、ユドヨノインドネシア大統領はインドネシアの温室効果ガス排出量を26〜41%削減すると発表。インドネシア政府はノルウェーとのパートナーシップによる「*REDD+」(途上国の森林減少・劣化に由来する温室効果ガス排出の削減)に調印。インドネシアの森林伐採が緩和され、その目的が達成されればREDD+はインドネシアに最高10億ドルの支援をもたらす。

インドネシア国家気候変動協議会(DNPI)によれば、インドネシアが抱える排出量の85%以上は現在、森林伐採、プランテーション開発等の土地利用によって起こる泥炭の分解や森林火災によって排出されている。

*REDD+: REDD+とはREDD(Reduce Emission from Deforestation and forest Degradation: 森林減少・劣化からの温室効果ガス排出削減)という考えに植林事業、森林保全の役割や森林の持続可能な管理等新たな対策を加えた森林の炭素貯蔵の増加を推奨する拡張概念。森林の減少や劣化による温室効果ガス排出量は世界の温室効果ガス排出量の20%を占めるため、気候変動対策に森林の保護は欠かせない。REDDは炭素を貯蔵する役割のある森林に経済価値をつけることで、豊かな森林を保持する発展途上国に伐採などから森林保護を誘因する対策。

当記事は原文記事の抄訳です。

CITATION: Mark Broich, Matthew Hansen, Fred Stolle, Peter Potapov, Belinda Arunarwati Margono and Bernard Adusei1 (2011). Remotely sensed forest cover loss shows high spatial and temporal variation across Sumatera and Kalimantan, Indonesia 2000–2008. Environmental Research Letters 6 (January-March 2011) 014010 doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/1/014010

Related articles

Will Indonesia’s big REDD rainforest deal work?

(12/28/2010) Flying in a plane over the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, rainforest stretches like a sea of green, broken only by rugged mountain ranges and winding rivers. The broccoli-like canopy shows little sign of human influence. But as you near Jayapura, the provincial capital of Papua, the tree cover becomes patchier—a sign of logging—and red scars from mining appear before giving way to the monotonous dark green of oil palm plantations and finally grasslands and urban areas. The scene is not unique to Indonesian New Guinea; it has been repeated across the world’s largest archipelago for decades, partly a consequence of agricultural expansion by small farmers, but increasingly a product of extractive industries, especially the logging, plantation, and mining sectors. Papua, in fact, is Indonesia’s last frontier and therefore represents two diverging options for the country’s development path: continued deforestation and degradation of forests under a business-as-usual approach or a shift toward a fundamentally different and unproven model based on greater transparency and careful stewardship of its forest resources.

Pulp plantations destroying Sumatra’s rainforests

(11/30/2010) Indonesia’s push to become the world’s largest supplier of palm oil and a major pulp and paper exporter has taken a heavy toll on the rainforests and peatlands of Sumatra, reveals a new assessment of the island’s forest cover by WWF. The assessment, based on analysis of satellite imagery, shows Sumatra has lost nearly half of its natural forest cover since 1985. The island’s forests were cleared and converted at a rate of 542,000 hectares, or 2.1 percent, per year. More than 80 percent of forest loss occurred in lowland areas, where the most biodiverse and carbon-dense ecosystems are found.